2010-2019: The Top 100 Films of the Decade

theatlantic.com

WATCH THE VIDEO:

Video playlist:

Dedicated to Eli Hayes, whose reviews encouraged me to check out some of the films which appear here. Rest easy.

These are not the best films of the decade. I don't mean that in a "this is my opinion, man, and opinions are subjective" sense (although that also applies); what I mean is that even I wouldn't assert that these are the best films of the decade, because I weighed them according to other criteria. I considered their artistic merit, to be sure, but I also considered what they mean to me personally, how they contributed to the evolution of cinema, and how they reflected the cultural movements of the 2010s. I wanted this list to be a time capsule, capturing both the breadth and depth of the decade.

I allowed myself to include a maximum of ONE film per director, largely to prevent Sion Sono and Denis Villeneuve from hijacking the list. Directors who would have had more than one movie on the list have their "honorable mentions" noted alongside the film I included.

For the purposes of this list, release year was determined by US release date, NOT including festival or limited runs.

First off, a few films which deserve…

HONORABLE MENTIONS (organized alphabetically):

1917

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

The Beguiled

The Big Sick

Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk

Birdman

Blind

The Breadwinner

Buzzard

The Cabin in the Woods

Call Me By Your Name

Chronicle

Columbus

The Edge of Seventeen

The Farewell

The Final Girls

Girlhood

Hale County This Morning, This Evening

Heart of a Dog

Hell or High Water

I Lost My Body

Long Day’s Journey Into Night

Magical Girl

Mission: Impossible - Fallout

mother!

My Life as a Zucchini

The Perks of Being a Wallflower

Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping

The Raid

Red State

A Separation

Slow West

Son of Saul

Spotlight

Spring

Summer of Sangaile

What We Do in the Shadows

Wildlife

The Wind Rises

Your Name.

Without further ado, here are…

2010-2019: The Top 100 Films of the Decade

100. The Assassin

Dir. Hou Hsiao-hsien

Writ. Hou Hsiao-hsien, Chu Tien-wen, Cheng Ah, Hsieh Hai-Meng

“The way of the sword is pitiless.”

hollywoodreporter.com

I finally fell in love with wuxia this decade after bouncing off it multiple times, but the 2010s didn’t have much to offer when it came to new entries in the genre (I was watching notable examples from the decade before: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, House of Flying Daggers, Hero). The 2010s did give us one at least one great wuxia experience, though, and The Assassin is unlike anything else I’ve seen in the genre—director Hou Hsiao-hsien takes a restrained, almost suffocating approach, suffusing every scene with long, lingering shots. Only occasionally does violence break out (I didn’t time it, but there can’t be more than a couple minutes of cumulative swordplay throughout the film), but when it does, it is like a flash of red lightning through the clouds, spattering blood across the rich tapestry of Mark Lee Ping-Bing (In the Mood for Love) and Yao Hung-I’s (Long Day’s Journey into Night) cinematography. The Assassin isn’t for everyone, but it’s worth a watch, and it has grown on me over multiple viewings.

99. One Cut of the Dead

Dir. Shinichiro Ueda

Writ. Shinichiro Ueda

“Holy cow! You could be an actor.”

businessinsider.com

One Cut of the Dead is difficult to talk about without spoiling; it is most effective when you go in knowing nothing and allow it to unravel on its own terms (although having it spoiled won’t ruin the movie by any means—I’m speaking from experience). So I’ll just say this: it makes zombies fresh and fun again. The reason I wanted to put it on this list, though, is because it reminded me of the primal joy of amateur filmmaking. There’s something so pure about making a movie with your friends, and I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a film which captures the nostalgia I have for that experience so elegantly. A true treasure.

98. The Avengers

Dir. Joss Whedon

Writ. Joss Whedon, Zak Penn

“If we can’t protect the Earth, you can be damned well sure we’ll avenge it.”

entertainment.directv.com

I have mixed feelings about the Marvel Cinematic Universe, but it felt wrong to make a list of the top hundred movies of the 2010s and not feature at least one entry from the most influential franchise of the decade. Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 is easily the best of the bunch, and the most important is arguable—I could conceivably make cases for Avengers: Infinity War (killing off half the cast, albeit temporarily, is still a wild swing for such a corporate product) or Avengers: Endgame (for all its flaws, capping off a 22-film franchise in satisfactory fashion is a notable and impressive feat). But ultimately, I had to go with The Avengers—the one that brought Iron Man, Captain America, Thor, Hulk, Black Widow, and Hawkeye together for the first time and proved that the whole thing could work. It remains a lot of fun all these years later, chock-full of strong setpieces and eminently quotable one-liners from writer/director Joss Whedon. The Avengers changed movies forever.

97. Get Out

Dir. Jordan Peele

Writ. Jordan Peele

“My dad would have voted for Obama a third time if he could’ve. Like, the love is so real.”

insider.com

I actually don’t like Get Out all that much; it’s a fine film, but it wouldn’t be anywhere near my personal top hundred movies of the decade. If I were making a list of films which were the most important in reflecting and reframing American culture in the 2010s, though, Get Out would earn the #1 slot—so it lands here at #97 as a compromise. Its genre elements dampen the power of its messages, but no movie this decade did more to capture the constant unease of being Black in America: the microaggressions and the pit-in-your-stomach terror that comes with the sight of a police car. My own feelings aside, to leave Get Out off this list would be nothing less than dishonest.

96. The Lego Movie

Dir. Phil Lord, Christopher Miller

Writ. Phil Lord, Christopher Miller, Dan Hageman, Kevin Hageman

“Blah, blah, blah. Proper name, place name, backstory stuff...”

warnerbros.com

This self-aware romp through tropes and clichés is a startling slice of all-ages fun, transforming what could have been—and, let’s be honest, still is—an advertising sledgehammer into a charming and irreverent reminder of the joy and wonder we can experience when we play with toys. The Lego Movie shines as satire, too, taking shots at everything from corporate greed to toxic positivity to the concept of the Chosen One. Even though I elected to give only the original film a spot on this list, I’d also like to give a shoutout to The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part, which is inferior to its predecessor only in its lack of novelty.

95. The Lure

Dir. Agnieszka Smoczyńska

Writ. Robert Bolesto

“All you need to do is have fun. The rest is easy.”

indiewire.com

Hey: a Polish musical about mermaids who sing at a nightclub and kill people! This is one of those cases where the premise is so fiendishly delightful that, even if it had been clumsily handled, it still might have had a shot at this list. The Lure is not clumsily handled, though—director Agnieszka Smoczyńska seamlessly weaves music and horror into a cult charmer that has no trouble living up to the delicious promise of its high concept spin on classic fairy tales. Don't miss it!

94. Chi-Raq

Dir. Spike Lee

Writ. Spike Lee, Kevin Willmott

“Repeat after me: I will deny all rights of access or entrance.”

chicagoreader.com

BlacKkKlansman got all the attention, but I’d like to put forward Chi-Raq as the best Spike Lee film this decade. It’s a bloated, heavy-handed mess, but it’s Spike Lee, so it’s a glorious, hilarious, heavy-handed mess, an adaptation of Lysistrata set in Chicago and shot through (literally) with an anger and an electric energy which bring it to life. Chi-Raq may have been overlooked, but it’s essential Lee.

93. Heaven Knows What

Dir. Josh Safdie, Benny Safdie

Writ. Josh Safdie, Ronald Bronstein, Arielle Holmes

“Would you forgive me if I die?”

indiewire.com

Based on the real-life experiences of star Arielle Holmes, Heaven Knows What is a hair’s breadth away from being a documentary (and it probably should have been; it would have jumped about fifty places up this list), but even fictionalized, it is nothing less than one of the most harrowing experiences put on a screen this side of Come and See. Portraying the life of a heroin addict on the streets of New York, Heaven Knows What is an anxiety-fueled descent into madness (a specialty of the Safdie Brothers, who went on to direct Good Time and Uncut Gems)—it is raw and uncompromising and utterly stripped of anything resembling sensationalism, and it is punctuated by one of the most devastating cut to credits I’ve ever seen. I’m glad I watched Heaven Knows What; I’m just not sure I could ever watch it again.

Josh & Benny Safdie honorable mention: Good Time

92. Personal Shopper

Dir. Olivier Assayas

Writ. Olivier Assayas

“You know how they say the dead watch over the living?”

rogerebert.com

Clouds of Sils Maria was a strong contender for this list, but I went with Personal Shopper as the superior Olivier Assayas film; for all it did well, Clouds’ clumsy attempts at satirizing the superhero movies churned out by Hollywood were too much of a stumbling block for me, whereas Personal Shopper is slyly and consistently oblique in its handling of tension and emotional texture. Utilizing the tropes and vocabulary of horror as metaphors for grief is nothing new, but Assayas handles it all with grace, sensitivity, an occasional light spook, and a knockout Hitchcockian setpiece involving texting on a train. If there was ever any doubt that Kristen Stewart was one of our finest working actresses, Personal Shopper will put those fears to rest.

Olivier Assayas honorable mention: Clouds of Sils Maria

91. Cam

Dir. Daniel Goldhaber

Writ. Isabelle Link-Levy, Daniel Goldhaber, Isa Mazzei

“Is this what you want?”

theverge.com

Unfriended walked so Cam could run. Daniel Goldhaber’s techno-thriller was one of Netflix’s best original cinematic offerings this decade (a low bar, admittedly), a smart and restrained slice of horror about that frustrating call with customer service after you get locked out of your account. Things are a bit more complicated for camgirl Alice/“Lola” (Madeline Brewer in a fierce, authentic performance), whose online persona is hijacked by some sort of digital monster which looks and sounds just like her. The monster never manifests physically. You never find out what it is or where it came from. It is pure existential dread, and it unlocks resonant themes about the intersection of identity and technology. It is refreshing, too, to see camming portrayed on-screen in a straightforward, unfetishized fashion, as work and creativity rather than salacious titillation.

90. Free Solo

Dir. Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, Jimmy Chin

“It’s obviously, like, much higher consequence.”

littlevillagemag.com

I was torn between putting Meru or Free Solo on this list: both are exceptional documentaries about climbers (two wildly different types of climbers, admittedly) from Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin, and I do feel like Meru is superior as a chronicle of human achievement. But I ultimately gave Free Solo the edge because it digs deeper into the culture and psychology of activities in which people put their lives at risk. It interrogates and is often critical of rugged individualism and how that intersects with (toxic) masculinity—this is complicated, however, by documentary subject Alex Honnold, who is implied to be neuroatypical. What right do we have to our own bodies? Our own lives? What if the things that make most people happy do not make us happy? Do we have the right to pursue that happiness if it might, by proxy, hurt those who love us? These questions bubble in the subtext of Free Solo. It wisely never attempts to answer them, but that they are raised at all makes this one of the best documentaries of the decade. (And if that isn’t enough, come on: check out that footage of Honnold free soloing El Capitan. Come on. Tell me that isn’t cool.)

Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi & Jimmy Chin honorable mention: Meru

89. Raw

Dir. Julia Ducournau

Writ. Julia Ducournau

“What do you eat?”

indiewire.com

Are you a person who enjoys French coming-of-age films in which graphic cannibalism is used as a heavy-handed metaphor for a young woman’s journey of sexual self-discovery? If so, then Julia Ducournau’s Raw is for you! (Just to be clear, I am a person who enjoys French coming-of-age films in which graphic cannibalism is used as a heavy-handed metaphor for a young woman’s journey of sexual self-discovery.) Raw is outlandish and outrageously entertaining, campy but also sharply written and sharply directed, fully aware of how silly it is but also willingly to take that silliness seriously—when you’re a teenager, desire in every form feels overwhelming, and Ducournau honors that emotional truth. Raw has all the makings of a cult classic.

88. Searching

Dir. Aneesh Chaganty

Writ. Sev Ohanian, Aneesh Chaganty

“I didn’t know her. I didn’t know my daughter.”

gamespot.com

One of the cinematic innovations I enjoyed seeing the most this decade was the “entire film takes place on screens” genre (is there a less-unwieldy term?), a sort of Gen Z descendant of the found footage genre. Unfriended—a wildly underappreciated movie—would have had a shot at this list if it hadn’t sacrificed the coherence of its mythology for a cheap cut-to-black jump scare. So the slot goes instead to Searching, a tightly-wound thriller about a father using technology to search for his missing daughter. The plot is competent and satisfying, albeit unremarkable, but director Aneesh Chaganty’s use of screens to keep the tension high and the momentum moving feels fresh enough to be notable when this type of filmmaking is so nascent. A fun ride.

87. Me and Earl and the Dying Girl

Dir. Alfonso Gomez-Rejon

Writ. Jesse Andrews

“My mom is gonna turn my life into a living hell if I don't hang out with you.”

cornellsun.com

Me and Earl and the Dying Girl takes many of the tropes I hate and spins them into a rich and realized tale about friendship and the ways in which we use narrative to shape our understanding of other people. Greg and Earl are two cinema-obsessed high schoolers who agree to make a movie for their friend Rachel, who is dying of cancer—they obsess over the Criterion Collection (just @ me next time), and their irreverence cloaks an emotional honesty which really resonated with me. Alfonso Gomez-Rejon’s direction evokes Wes Anderson (if Wes Anderson made films I actually liked; don’t @ me) and Olivia Cooke turns in a textured performance as Rachel. Jesse Andrews, who is also the author of the novel upon which this adaptation is based, wrote the screenplay, and it is sharper and smarter than its source material—add another tally to the “movie is better than the book” column.

86. Moana

Dir. Ron Clements, John Musker

Writ. Ron Clements, John Musker, Chris Williams, Don Hall, Pamela Ribon, Jared Bush, Aaron Kandell, Jordan Kandell

“You’re welcome.”

slashfilm.com

Tangled and Frozen showed a great deal of promise for Disney’s new era of 3D animation, but they lacked the magic and the spark of true classics. Not so with Moana. One of their best original works in years, it shines with inventive visual and textual storytelling and delivers rousing musical numbers the likes of which the studio hasn’t mustered since the late ‘90s. Auli’i Cravalho is nothing less than transcendent as Moana herself, while Dwayne Johnson and (briefly) Jemaine Clement provide comedic relief. Pulling on everything from Polynesian culture to Mad Max to (in an awkward misstep) Twitter, Moana bursts with gorgeous imagery and engages both the mind and the heart.

85. Breathe

Dir. Mélanie Laurent

Writ. Mélanie Laurent, Julien Lambroschini, Anne-Sophie Brasme

“Tell me a secret.”

metacritic.com

We all knew Mélanie Laurent was a powerhouse in front of the camera, but it turns out she’s a talent behind it, too: Breathe is directed within an inch of its life, like an athlete pushed to the limits of their endurance—it’s all muscle, no fat, a ruthlessly precise thriller with no space in its heart for mercy. Laurent demonstrates her formal control with tracking shots that would put a seasoned director to shame, and she has an intimate understanding of the hyperbolic gravity given to every interaction in teenage relationships. Joséphine Japy and Lou de Laâge shine in the lead roles. The climax arguably slips into camp, but don’t let that deter you from seeking out this overlooked gem.

84. Queen of Earth

Dir. Alex Ross Perry

Writ. Alex Ross Perry

“You don’t know anything about me.”

nydailynews.com

It’s been years since I saw Queen of Earth, and to be honest, I don’t really remember what happened. But I do remember how it made me feel: like I was constantly on the verge of an anxiety attack (director Alex Ross Perry has a particularly talent for evoking this response, which he turned up to eleven in Her Smell). Elisabeth Moss’ Kubrickian stare, the frayed-nerve score, the way the camera leers and lingers, like a voyeur peeking around a corner or through a door slightly ajar—this riff on Persona is saturated with tension, and a chill still crawls down my spine every time I think about it. If that’s not enough to earn it a place in my top hundred films of the decade, I don’t know what is.

83. Game Night

Dir. John Francis Daley, Jonathan M. Goldstein

Writ. Mark Perez

“I’ve always enjoyed the camaraderie of good friends competing in games of chance and skill.”

empireonline.com

With mainstream comedies continuing their insufferable descent into glorified celebrity improv in the 2010s, Game Night is a breath of fresh air: every moment is—or at least feels—constructed and intentional. The script is sharp. Care is given to the camerawork and visuals. Any potential bloat has been pared away by the snappy editing. Jason Bateman, Rachel McAdams, and Kyle Chandler turn in some of their strongest comedic performances to date, but Jesse Plemons (one of this decade’s best dramatic actors) steals the show as Gary Kingsbury, transforming vaguely-threatening dialogue into the funniest lines I’ve heard in ages (“How can that be profitable for Frito-Lay?”). Game Night is what happens when a movie is made with an actual vision instead of a charismatic performer riffing in front of a camera, and the result is the best mainstream comedy to be released in years. This is a winner.

82. A Most Violent Year

Dir. J.C. Chandor

Writ. J.C. Chandor

“You’re not gonna like what will happen once I get involved.”

thesouloftheplot.wordpress.com

My self-imposed parameters only accorded me one J.C. Chandor film on this list, and it was a hard call between All Is Lost and A Most Violent Year; the former is an elegant fable, enthralling despite its minimal dialogue thanks to Chandor’s assured direction and Robert Redford’s towering performance, but I settled on the latter as the superior movie. Oscar Isaac (never better) and Jessica Chastain (rarely better) crackle as Abel and Anna Morales, a couple attempting to stabilize a nascent company and best their competition in 1981 New York. A Most Violent Year has nothing new to say when it comes to crime dramas about the false promise of the American dream, but between the performances and the moody cinematography conjured up by Bradford Young—it evokes the washed-out weariness of a winter morning—it’s easy to find a place for Chandor’s third feature on this list.

J.C. Chandor honorable mention: All Is Lost

81. Calvary

Dir. John Michael McDonagh

Writ. John Michael McDonagh

“I’m going to kill you, Father.”

theguardian.com

A high concept for the ages: during a confession, a member of a priest’s congregation threatens to kill him in one week’s time—vengeance for the abuse they suffered as a child at the hands of another church official. But this is not a mystery-thriller so much as a meditation on mortality, sacrifice, forgiveness, and atonement. Brendan Gleeson turns in what may well be the best performance of his career as Father James Lavelle, and director John Michael McDonagh guides his gloomy journey with a deft and deliberate hand. Despite a didactic conclusion that lacks the richness and complexity of the film which precedes it, Calvary is ultimately a melancholy treat.

80. Coco

Dir. Lee Unkrich

Writ. Lee Unkrich, Matthew Aldrich, Jason Katz, Adrian Molina

“Remember me, though I have to say goodbye...”

teenvogue.com

I cannot speak to the cultural elements in Coco or how well Pixar portrays their nuances, but I can say that the animation studio has delivered yet another aesthetically vibrant and emotionally resonant tale weakened only by an uninspired third-act villain. The rest of the film reckons (predictably) with what death takes from us, but also (less predictably) with what memory, or the lack thereof, takes from us, and what it can give us back if we can and choose to keep it alive. Both sweet and heartbreaking, Coco is a winning foray into Mexico—hopefully the first, and not the only—for Pixar, a rich and mature story which ranks among their best.

79. In Jackson Heights

Dir. Frederick Wiseman

“We give our lives and our sweat so this nation moves forward.”

rogerebert.com

At Berkeley and Ex Libris: The New York Public Library were both strong contenders, but In Jackson Heights remains my favorite Frederick Wiseman film of the 2010s (although that may be the result of factors external to the movie itself). This documentary explores not the topography of an institution, as Wiseman so often does, but of a community—New York City’s Jackson Heights, one of the most diverse neighborhoods in the world. To see so many different people of so many different skin colors, speaking so many different languages, sharing so many different cultures, all struggling to learn and to communicate and to work together, is singularly thrilling to watch while living in an America which has suffered under Trump’s reign. To say In Jackson Heights is uplifting, although true, is insufficient. This is not a portrait of people living in total harmony, but something deeper and richer, a chronicle of humanity as a spectrum and the work we do to contrast or complement one another. A breathtaking achievement.

Frederick Wiseman honorable mentions: At Berkeley, Ex Libris: The New York Public Library

78. Swiss Army Man

Dir. Daniel Scheinert, Daniel Kwan

Writ. Daniel Scheinert, Daniel Kwan

“Is this crying? I don’t like it. It’s wet and uncomfortable.”

vanityfair.com

Swiss Army Man is a movie about a man who befriends a farting corpse which propels him across the sea—do I really need to justify why I included it in my top hundred films of the decade? Fine, fine. I will say that Swiss Army Man reminded me in many ways of the works of Shakespeare: it lures you in with the lowest of low-brow humor, and then it hits you with real emotions and resonant themes that are so much more meaningful in juxtaposition. It’s a sensitive and thoughtful portrayal of love, sexuality, friendship, and masculinity—keenly filtered through a self-awareness of the flimsy societal constructs which have accumulated around them—and the absolute absurdity of its premise makes it more difficult to forget than your average feel-good drama.

77. The End of the Tour

Dir. James Ponsoldt

Writ. Donald Margulies

“We are both so young. He wants something better than he has. I want precisely what he has already. Neither of us knows where our lives are going to go.”

celluloidandwhiskey.com

Based on the book by Rolling Stone reporter David Lipsky and framed by allusions to David Foster Wallace’s suicide, The End of the Tour dramatizes Lipsky’s five-day interview with Wallace while he was on book tour shortly after the publication of Infinite Jest in 1996. The two men discuss what it means to live in a world on the verge of major cultural and technological shifts, and how to be a good artist and a good person in that world; the movie makes no effort to reckon with Wallace’s mental health or his problematic legacy—doing either would have been beyond its intimate scope—but it grounds one of the most legendary figures in American literature with a stellar performance from Jason Segal and attempts to unpack the complexity of envy.

76. Phoenix

Dir. Christian Petzold

Writ. Christian Petzold, Harun Farocki, Hubert Monteilhet

“I no longer exist.”

rogerebert.com

Christian Petzold turns Vertigo on its head in Phoenix, the story of a woman who undergoes facial reconstruction surgery after surviving a WWII concentration camp and returns to her husband; she reminds him of his wife, but he does not realize it is actually her, and so she attempts to discover whether he is responsible for selling her out to the Nazis. This is a taut thriller, clocking in at roughly ninety minutes, but it has more on its mind than escalating tension. Phoenix reckons with identity, disability, and the crisis of post-war Germany, and flipping the gender dynamic of Hitchcock’s classic reveals new nuances about how the patriarchy distorts the nature of perception and subjectivity. Nina Hoss turns in an objectively great performance in the lead role as Nelly, and it all culminates in a gut-punch finale.

Christian Petzold honorable mention: Transit

75. Mustang

Dir. Deniz Gamze Ergüven

Writ. Alice Winocour, Deniz Gamze Ergüven

“I slept with the entire world.”

variety.com

This Turkish film is a perfect example of how story structures can unexpectedly elucidate themes when they are not beholden to genre. Mustang is structured like a slasher movie—but instead of being killed, the five sisters who form the focus of the story are shuffled off into marriages. It’s quite clever, and it’s a choice which elevates Mustang above similar films. Performances are also strong across the board, and Warren Ellis delivers a rich and textured score. Don’t miss this movie; Mustang is one of the decade’s most underappreciated gems.

74. Moonlight

Dir. Barry Jenkins

Writ. Barry Jenkins, Tarell Alvin McCraney

“At some point, you gotta decide for yourself who you gonna be. Can’t let nobody make that decision for you.”

theatlantic.com

I wasn’t sure if I should put Moonlight or director Barry Jenkins’ follow-up, If Beale Street Could Talk, on this list; the latter may be the better film (I’d need to watch them back-to-back to be sure), but I ultimately went with Moonlight because it feels more revelatory in the history of cinema. Despite the debacle at the Academy Awards, a movie about a gay Black man gaining such widespread recognition is still something to celebrate, and the grace and sensitivity with which Jenkins treats the subject matter makes it more than just a cheap diversity swing. I find Moonlight difficult to connect with due to the casting of multiple actors as the same character, but the performances are magnificent enough and the cinematography is gorgeous enough to make up for it.

Barry Jenkins honorable mention: If Beale Street Could Talk

73. Locke

Dir. Steven Knight

Writ. Steven Knight

“No matter what the situation is, you can make it good.”

time.com

I wasn’t sure if I should put Locke on this list, because I wanted to highlight movies which utilize the tools of cinema to tell their story and this is a film which I feel would be better suited to the stage (or even an audio drama) than to the screen: Tom Hardy plays a character making phone calls in his car while driving, and the drama takes place almost entirely through dialogue—there isn’t much of a visual element. But that drama was ultimately too good to leave off. Writer/director Steven Knight’s script has the precision of clockwork, and Tom Hardy has the acting chops to pull off a performance that gives him almost nothing to work with. This is riveting stuff, well worth a spot on this list.

72. Logan

Dir. James Mangold

Writ. James Mangold, Scott Frank, Michael Green

“Nature made me a freak. Man made me a weapon. And God made it last too long.”

businessinsider.com

I’ll take clumsy social commentary over soulless corporate bombast any day of the week, so it won’t surprise you to learn that I’m generally more forgiving of the X-Men franchise than I am of the MCU (which isn’t to say that X-Men never fell victim to soulless corporate bombast or that the MCU is 100% apolitical, but we’re talking big picture here). The former franchise peaks with Logan, a glorious send-off for its key character: Hugh Jackman’s Wolverine. Its vision of the future is fully-realized with just a few key visual details, and it feels like the perfect culmination of Logan’s story despite being largely disconnected from the rest of the franchise. Co-stars Dafne Keen and Patrick Stewart shine, and Jackman himself delivers the pathos you only get by playing a character for seventeen years. I still feel like the full potential of the X-Men characters has yet to be tapped, but even if that never happens, Logan is a hell of a high note to go out on. What a ride.

71. Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol

Dir. Brad Bird

Writ. Bruce Geller, Josh Appelbaum, André Nemec

“Your mission, should you choose to accept it...”

empireonline.com

Mission: Impossible - Fallout gunned for the crown with some truly breathtaking action sequences, but Ghost Protocol remains the best Mission: Impossible film of the decade (and of the entire franchise, for what it’s worth). With economic editing and camerawork, director Brad Bird seamlessly blends and balances humor and thrills; unlike Rogue Nation and Fallout director Christopher McQuarrie, Bird understands that Mission: Impossible is at its strongest when it’s campy, and he wisely allows the goofier elements of the franchise to flourish. His setpieces are knockouts, too—the famous Burj Khalifa climb anchors the movie at its midpoint, but the Kremlin infiltration and the Mumbai sequence also shine by focusing in on other members of the IMF team. Ghost Protocol does have its weak points (a forgettable villain and a climactic final showdown which is, frankly, anticlimactic), but they aren’t enough to keep it off this list; I like to think of them as reminders that the eventual best entry in the franchise may still be yet to come.

70. Spring Breakers

Dir. Harmony Korine

Writ. Harmony Korine

“Just pretend it’s a video game. Like you’re in a fucking movie.”

npr.org

Like a neon sign blazing in the night, Spring Breakers is satire without subtlety—and yet, its candy-coated descent into madness is so garish and so hyperbolic that it circles all the way back around to something that wields an unearthly sort of power. Casting former Disney stars Selena Gomez and Vanessa Hudgens is a clever opening gambit, but director Harmony Korine takes things to the next level with an utterly unrecognizable James Franco as Alien, who ushers them into a world of drugs and violence. You’ll never hear Britney Spears the same way again.

69. Fury

Dir. David Ayer

Writ. David Ayer

“Best job I ever had.”

freep.com

Yes, a David Ayer movie made it into my top films of the decade. Deal with it. This is a far cry from Suicide Squad: Fury is in many ways a generic WWII movie—albeit an impeccably crafted one—and I wouldn’t have given it a second thought if that’s all it was, but there’s one scene near the middle of the film which is so tense and so textured (if you’ve seen it, you know the one I’m talking about; if you haven’t, I won’t spoil it) that I’ve been thinking about it for years, and it single-handedly earned the movie a place on this list. Howard Hawks said that a good movie is “Three great scenes, no bad ones.” I’ll settle for one great scene and no bad ones. Welcome to my top films of the decade, Fury.

68. First Reformed

Dir. Paul Schrader

Writ. Paul Schrader

“Every act of preservation is an act of creation.”

variety.com

Writer/director Paul Schrader and lead actor Ethan Hawke are both at the top of the their game in this story of the pastor of a historic church who, after meeting two young activists, becomes obsessed with impending environmental collapse and whether he is complicit in destroying God’s creation by failing to act against that destruction. First Reformed feels like the cinematic equivalent of being dropped into the Mariana Trench: every frames feels like it is about it to be crushed by unbearable, overwhelming pressure—both spiritually and literally, in light of the 4:3 aspect ratio. But in Schrader’s hands, control and claustrophobia (and the occasional striking use of color) become instruments of catharsis, and he when he finally opens a valve to release the pressure, the effect is nothing less than breathtaking.

67. Beyond the Hills

Dir. Cristian Mungiu

Writ. Cristian Mungiu

“The man who leaves and the man who comes back are not the same.”

npr.org

You’d be forgiven for not knowing that Beyond the Hills is based upon a true story: this tale of a friendship between two young women falling to pieces after one of them joins an Orthodox monastery in Romania has all the trappings of allegory. But like director Cristian Mungiu’s masterpiece, 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days (one of the best movies I’ve ever seen and one which I will likely never watch again), I am not interested in what Beyond the Hills is saying so much as how it says it. This is Romanian New Wave, and it’s Mungiu, so the film is formal and precise and minimalist to the point of being excruciating, but I found myself so invested in every frame that I could not look away. Although it lacks the structural sharpness of 4 Months—Beyond the Hills is a bit bloated and probably could have benefited from losing a half hour or so—it remains a shining example of why Romanian New Wave is my favorite cinematic movement and why Mungiu is its master, even if it is too depressing to ever lay eyes on again. This is powerful stuff.

66. We Need to Talk About Kevin

Dir. Lynne Ramsay

Writ. Lynne Ramsay, Rory Stewart Kinnear, Lionel Shriver

“You don’t look happy.”

taylorholmes.com

Colors. Or, more specifically: color. We Need to Talk About Kevin is absolutely soaked, absolutely dripping, in red—it’s not subtle, but then again, there’s nothing subtle about mass murder. The film is relatively rote in regard to Kevin himself (Ezra Miller’s performance is hypnotic, but the movie gets uncomfortably close to implying that “guns don’t kill people, people kill people!”), but it shines when it maintains its focus on Kevin’s mother, played masterfully by Tilda Swinton. A fiery rant from Laura Dern’s character in Marriage Story describes how society expects more from mothers than from fathers, but those expectations are actually portrayed in We Need to Talk About Kevin when society turns its wrathful gaze on Swinton’s character in the wake of her son’s murderous rampage. Why didn’t she raise him better? Why didn’t she teach him right from wrong? Why isn’t she being punished? We Need to Talk About Kevin is a particularly interesting exploration of mass murder, but it is a phenomenally interesting exploration of masculinity and motherhood and the ways in which society sets boys and mothers up, grooms them, for failure.

65. Marriage Story

Dir. Noah Baumbach

Writ. Noah Baumbach

“Getting divorced with a kid is one of the hardest things to do. It’s like a death without a body.”

nytimes.com

Noah Baumbach has made a lot of good movies, but he gets close to greatness for the first time with Marriage Story, in which Adam Driver and Scarlett Johansson play a couple who become entangled in protracted divorce proceedings. The film feigns at bipartisanship despite presenting Driver’s character in a far more sympathetic light than Johansson’s, and it can be difficult at times to feel bad for characters who are so white and so wealthy, but Baumbach’s formal control and the murderers’ row of knockout performers (even alongside peak Driver, Johansson, Wever, and Alda, Laura Dern still manages to stand out; “He didn’t even do the fucking!”) overcame these misgivings for me. This doesn’t feel like the culmination of Baumbach’s career—this feels like a promise of what is still to come.

64. Sherpa

Dir. Jennifer Peedom

“He keeps going to the mountain.”

theguardian.com

I have a soft spot for documentaries about climbers and climbing, and the 2010s gave us some real gems (Meru, Free Solo), but Sherpa tops them all because it provides a desperately-needed new angle on the genre: it interrogates the racial, economic, and religious dynamics of climbing Everest, of the ways in which white people have taken and continue to take advantage of the local Sherpa people to elevate their personal glory, and the ways in which the Sherpa people have become dependent on those dynamics for their macro and micro welfare. This is all framed in light of a 2014 avalanche which killed sixteen Sherpas on Everest and the strike they staged in the aftermath. It’s an intimate and deeply personal film, but it’s also a microcosm for a struggle that is continuing to happen worldwide—you may not be a white person rich enough to scale Everest, but if you’re watching Sherpa, you are likely still complicit, directly or indirectly, in the exploitation of BIPOC laborers. This is a sobering, revelatory movie, and it’s the shot in the arm the genre needed; mountain climbing documentaries will never be the same in light of the work director Jennifer Peedom has done.

63. Victoria

Dir. Sebastian Schipper

Writ. Sebastian Schipper, Olivia Neergaard-Holm, Eike Frederik Schulz

“You don’t have to do this.”

filmfantravel.com

One of the longest legitimate single-take films (it was the longest when it was made), Victoria follows a young Spanish woman in Berlin who meets some local boys during a night out (you’ll have the best experience with the movie if you don’t know any more than that). Like all long shots, it runs the risk of becoming a self-congratulatory gimmick, and I’m not unsympathetic to viewers who think it does just that. But in the case, I believe the technical merits of the gimmick are good enough to warrant it a place on this list, and there is something more substantive going on: Victoria is about what happens when you lack the agency and the autonomy to say NO, what happens when you are lost and alone and so desperate to find fellowship that you’ll do anything to belong. This is hardly a character deep dive, but these thematic shades give Victoria an edge over the shallow thrills of 1917, and the legitimacy of its single take makes it more impressive than the fun but self-important Birdman.

62. Cloud Atlas

Dir. Tom Tykwer, Lilly Wachowski, Lana Wachowski

Writ. Tom Tykwer, Lilly Wachowski, Lana Wachowski, David Mitchell

“What is an ocean but a multitude of drops?”

archdaily.com

Cloud Atlas is held back by one egregious misstep: actors are cast in multiple roles, which wouldn’t be so bad if it hadn’t led to more than one occurrence of yellowface (the makeup is truly terrible, too). The film is trying to get at this theme of “we are connected across time and space, regardless of race or sex or gender,” but that message is reinforced in other ways throughout the movie, and in this particular respect it gets dangerously close to saying “I don’t see color.” It would be insincere of me to not call this out, but having done so, I still love Cloud Atlas. It slips effortlessly between genres—the sci-fi Neo Seoul sections are particularly thrilling—with the assistance of a magnificent score, and it even compensates for the lack of the pyramidal structure of the novel upon which it is based with impeccable editing that draws the multiple timelines together in a way that elucidates their thematic resonance, like a precursor to Gerwig’s Little Women. Cloud Atlas should have been a mess; instead, it’s a minor miracle.

61. Django Unchained

Dir. Quentin Tarantino

Writ. Quentin Tarantino

“Kill white people and get paid for it? What’s not to like?”

nydailynews.com

Tarantino’s films have been getting progressively weaker since his masterpiece (that would be Inglourious Basterds, in case you were mistakenly thinking of another movie), but it’s a long way down from those heights: Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood fell short for me, but The Hateful Eight still could have easily earned a spot on this list. That said, Django Unchained remains Tarantino’s best work this decade—the writing is predictably delicious (“Damn, I can’t see fuckin’ shit outta this thing!”), the cast shines (especially a scenery-chewing Leonardo DiCaprio as Calvin Candie), and it creates a cathartic (if superficial) counterpoint to 12 Years a Slave, which was released the same year. Django Unchained is an outrageously entertaining ride. Bye, Miss Laura!

Quentin Tarantino honorable mention: The Hateful Eight

60. Casting JonBenet

Dir. Kitty Green

“Do you know who killed JonBenet Ramsey?”

vox.com

I’m a sucker for meta-documentaries. Netflix’s Casting JonBenet is one of the best to come around this decade: focusing on the casting process for a film about the murder of JonBenet Ramsey, it picks apart the American obsession with true crime—an obsession kickstarted by Serial and Making a Murderer and mocked by American Vandal and A Very Fatal Murder—and, in particular, the way Americans convince themselves that they’ve solved the crime or understand the people involved based on only a passing cultural familiarity. Casting JonBenet is more than that, though. It also touches on how the pop culture machine transforms tragedy into entertainment; it is simultaneously sickening and outrageously funny (in a cringey sort of way), a strange and baffling oddity extracted from between the meshed gears of warped psychologies and predatory industries. I love it.

59. I Am Easy to Find

Dir. Mike Mills

Writ. Mike Mills

“She is born...”

consequenceofsound.net

I implemented a “one movie per director” rule for this list, but I’m making an exception for Mike Mills because I Am Easy to Find is a short film set to tracks from The National’s album of the same name and feels quite different from a feature-length narrative experience (you’ll find the other Mills movie higher up on this list). Chronicling the life a woman from birth to death, portrayed at all ages by an astounding Alicia Vikander, I Am Easy to Find is a work of startling elegance and vision, textured with emotional highs and lows, exceptional music, and crisp filmmaking. One of my favorite aspects of cinema this decade was how quieter, more intimate, smaller scale works—the kind you get when a few talented, interesting people get together between bigger projects—became more widely distributed and easier to access. Joss Whedon’s Much Ado About Nothing is another notable example of this, as are Jonathan Glazer’s The Fall and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Anima and Valentine, but none are better than I Am Easy to Find.

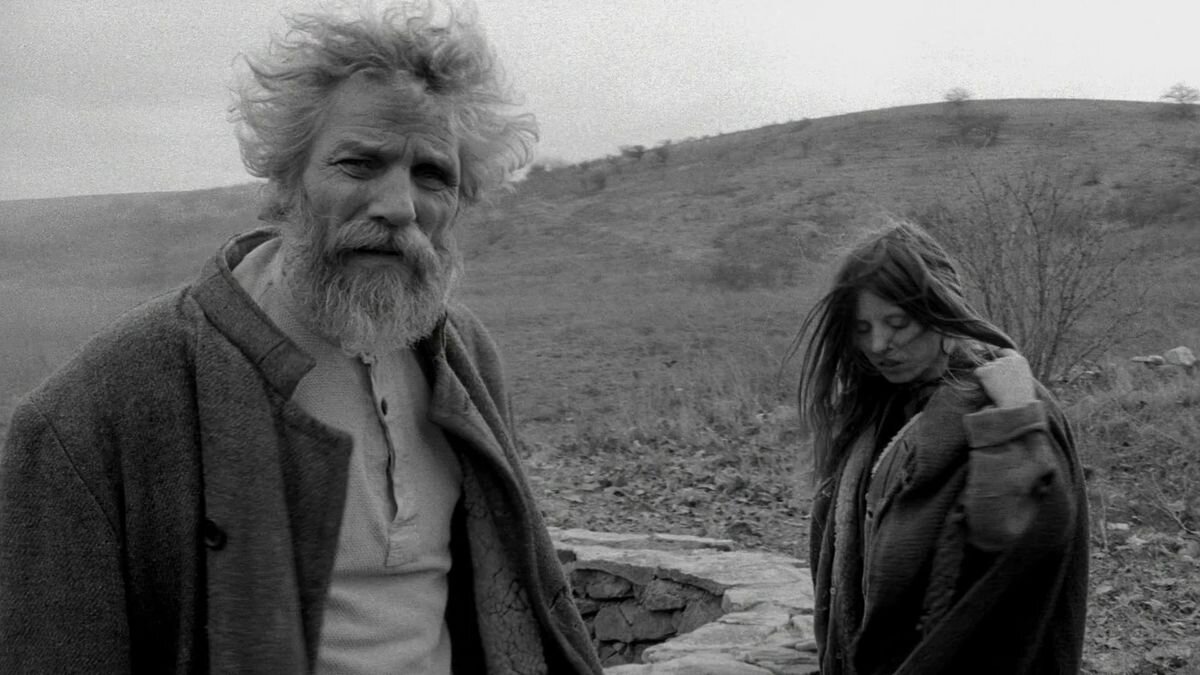

58. The Turin Horse

Dir. Béla Tarr, Ágnes Hranitzky

Writ. Béla Tarr, László Krasznahorkai

“We do not know what happened to the horse.”

letterboxd.com

The final film from Hungarian master Béla Tarr prior to his retirement, The Turin Horse strips all the Hollywood glamour and grandeur from the apocalypse. Following two potato farmers, a father and daughter, and a horse—presumably the same horse whose whipping triggered Nietzsche’s breakdown in 1889, as described at the beginning of the movie—The Turin Horse chronicles their daily routine and monotonous crawl into oblivion. The world is literally colorless. The wind scours, as if desperate to scrape the Earth clean. Darkness descends. Like The Red Turtle, The Turin Horse is so empty of plot that it opens itself up to almost any allegorical implication, but those implications always end with a long slow defeat. The movie, however, is anything but a defeat: it is an elemental experience, the crowning achievement of a career.

57. The Tribe

Dir. Myroslav Slaboshpytskyi

Writ. Myroslav Slaboshpytskyi

“This film is in sign language. There are no translations, no subtitles, no voice-over.”

rogerebert.com

These words open The Tribe, Myroslav Slaboshpytskyi’s Ukrainian drama about a young man who becomes tangled up in a criminal organization at a boarding school for the Deaf. I’ve soured somewhat on the film over the years because, beneath the “gimmick” and the relentless technical formality, the story is a gratuitously bleak—frankly cliché—exercise in nihilism and misery porn. But I haven’t soured on it enough to leave it off this list: I love art that forces you to engage with it in unconventional ways, and The Tribe is nothing if not that. If you’re not fluent in Ukrainian Sign Language, you will need to put down your phone and parse what is happening from the behavior of the actors. The process is engaging, even thrilling, and uniquely satisfying. For all its faults, this is a movie experience you won’t soon forget.

56. Burning

Dir. Lee Chang-dong

Writ. Lee Chang-dong, Haruki Murakami, Oh Jung-mi

“I’ll do anything for fun.”

empireonline.com

This adaptation of the Haruki Murakami short story “Barn Burning” is a deliciously slow...uh, burn. Director Lee Chang-dong is far more subtle here than in previous movies such as Poetry and Secret Sunshine; few films exist so wholly in liminal spaces, infused with tension and paranoia and uncertainty. Steven Yeun shines as Ben, an enigmatic Gatsby-esque figure who insinuates himself into the lives of Lee Jong-su and Shin Hae-mi (Yoo Ah-in and Jeon Jong-seo, respectively, also turn in solid performances), and master cinematographer Hong Kyung-pyo (who went on to shoot Parasite) extracts every drop of discomfort from the 2.5-hour runtime. Burning is a scorcher.

Lee Chang-dong honorable mention: Poetry

55. The Red Turtle

Dir. Michael Dudok de Wit

Writ. Michael Dudok de Wit

sfweekly.com

This dialogue-less story of a man who becomes stranded on an island and encounters a red turtle who transforms into a woman is told with a minimalism Hemingway would appreciate; like The Old Man and the Sea, you can apply almost any allegory you want to its framework and it will resonate with the power of metaphor and symbolism. If nothing else, the animation is achingly beautiful, and I was compelled by how it portrayed both the macro and the micro aspects of daily life. I was going to describe The Red Turtle as a film which is simultaneously empty and full, but on second thought, I believe it’d be more accurate to say that The Red Turtle is a film which is full of negative space.

54. Wolf Children

Dir. Mamoru Hosoda

Writ. Mamoru Hosoda, Satoko Okudera

“Why is the wolf always the bad guy?”

screenanarchy.com

I’ve enjoyed every film I’ve seen from director Mamoru Hosoda, but I sometimes find his work to be saccharine when he seems to be aiming for sentimentality. Wolf Children strikes a perfect balance. A young woman has two children with a werewolf, and she is forced to raise them on her own after the father is killed; the kids are both part-wolf and part-human, but Ame chooses to live as a wolf and Yuki chooses to live as a human. It’s not a particularly subtle metaphor, and yet it is allowed to play out with such emotional honesty that I found myself deeply moved. The story of Hana, the mother, is also given its due. Wolf Children may lack the richness and complexity of a Miyazaki masterpiece, but I loved its simple elegance, and I will be returning to it again and again. A true treasure, well-deserving of a spot on this list.

53. Eighth Grade

Dir. Bo Burnham

Writ. Bo Burnham

“But it’s like, being yourself is, like, not changing yourself to impress someone else.”

nytimes.com

I waffled between putting Eighth Grade or The Edge of Seventeen on this list; they deal with similar subject matter through slightly different lenses, and they’re both excellent movies, but Eighth Grade ultimately felt like the fresher and more invigorating film. I can’t recall many movies which capture the awkwardness of growing up quite so elegantly, and I can’t recall any other movie which captures the nuances of growing up in the 2010s with such finesse. Director Bo Burnham is completely in his element here, showcasing the ways in which social media and technology are intertwined with the dynamics of school and interpersonal interaction, and he flavors the film with just the right amounts of humor and pathos. Elsie Fisher is nothing less than a revelation in the lead role. I can’t wait to see more from both her and from Burnham, because Eighth Grade is truly something special.

52. A Ghost Story

Dir. David Lowery

Writ. David Lowery

“I’m waiting for someone.”

theedgesusu.co.uk

A Ghost Story reminds me of Equus (or any great work of theatre, really, or even Dogville if you want to stay cinema-oriented): it leans into and draws attention to its own artificiality, and then it wields that framework as a springboard for unexpected pathos. Casey Affleck’s character dies and then returns to his wife as a ghost, invisible to her but visible to the viewer as a figure wearing a simple white sheet. In a lengthy unbroken take, he watches Rooney Mara eat a pie. In an elegant montage, he watches her leave the house every morning. In a humorously subtitled exchange, he communicates with the ghost next door. A Ghost Story captures not only the keenness of grief, but the mundanity of it, the boredom and the routine and the weight of the wait as time grinds away day after day. It’s a lovely little story, richer and more resonant than any of David Lowery’s big-budget pictures.

51. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

Dir. Edgar Wright

Writ. Edgar Wright, Michael Bacall, Bryan Lee O’Malley

“If your life had a face, I would punch it.”

syfy.com

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World doesn’t quite hold up against the series of graphic novels upon which it is based, largely because the story is so condensed that it doesn’t have time to fully interrogate Scott’s own toxicity, but it remains an outrageously entertaining and infinitely quotable film; filled with stylistic flourishes and edited within an inch of its life, Edgar Wright’s masterpiece is a movie I have found myself returning to time and time again over the years. For all its faults, I still love Scott Pilgrim, and its visual identity is so distinctive that I couldn’t bear to leave it off this list. There was nothing else like it this decade.

50. Anomalisa

Dir. Charlie Kaufman, Duke Johnson

Writ. Charlie Kaufman

“I think you’re extraordinary.”

rollingstone.com

Synecdoche, New York is a tough act to follow, but Charlie Kaufman’s second feature as director is full of lovely little details which make it memorable in its own right. During his stay at a hotel, motivational speaker Michael meets and becomes obsessed with a woman named Lisa (she is the only other character not voiced by Tom Noonan, a wonderful way to put the viewer in Michael’s head); Kaufman uses this obsession—and the audience’s complicity in Michael’s perspective—to ruthlessly critique the concept of the “nice guy.” This comes through most clearly during a scene in which Lisa sings “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun” for Michael, and he tells her how beautiful it is—by interrupting her. Wickedly funny, wicked smart, and wickedly subversive in all the right ways, Anomalisa is another winner from Kaufman.

49. Annihilation

Dir. Alex Garland

Writ. Alex Garland, Jeff VanderMeer

“I think you’re confusing suicide with self-destruction.”

indiewire.com

Ex Machina was a promising directorial debut from novelist and screenwriter Alex Garland, but he steps up his game in this adaptation of Jeff VanderMeer’s skin-crawling novel about a group of scientists who investigate an area (“Area X” in the novel, “The Shimmer” in the movie) where plants and animals have begun to mutate in strange ways. Annihilation loses some of the subtleties and grace notes which made the novel so good, but it compensates with striking imagery, an inventive horror sequence unique to the film, and an eerie climactic showdown which ranks among the best scenes of the decade. It may be rough around the edges, but science fiction cinema is rarely this distinctive or this memorable; I am so glad Alex Garland gave it to us.

Alex Garland honorable mention: Ex Machina

48. The Witch

Dir. Robert Eggers

Writ. Robert Eggers

“Wouldst thou like to live deliciously?”

npr.org

The Witch is the best horror film since at least The Blair Witch Project in 1999, maybe even The Shining in 1980. Don’t @ me. Excruciating in its attention to period detail, Robert Eggers’ debut feature takes place in 1630s New England and follows a family that strikes out on their own after being banished from a Puritan colony; now living near the woods, they are plagued by encounters with a mysterious witch and tensions flare. Game of Thrones veterans Ralph Ineson and Kate Dickie feel like they’ve stumbled out of the 17th century, and breakout star Anya Taylor-Joy is hypnotic in the lead role. Frayed-nerve sound design and long, lingering zooms lend The Witch a slow burn quality, but it turns up the heat for an explosive, cathartic finale which cements it as nothing less than one of the greatest horror movies of all time.

47. Taxi

Dir. Jafar Panahi

Writ. Jafar Panahi

“You’re making a movie, right?”

npr.org

Taxi is a film you won’t fully understand without context: in 2010, Iranian director Jafar Panahi was banned by his country’s government from making movies for twenty years. He is perhaps most famous for making This is Not a Film the following year, a home video which interrogates what exactly defines a “film.” It was smuggled out of Iran on a flash drive hidden in a cake and shown at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival. In Taxi, Panahi pretends to be a taxi driver, picks up various passengers around Tehran, and records his conversations with them. Like Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson, there isn’t much here in the way of plot—but that’s not the point. This is a tribute to life and to love and to cinema...and let’s be honest, aren’t those all the same thing?

Jafar Panahi honorable mention: This is Not a Film

46. Star Wars: The Last Jedi

Dir. Rian Johnson

Writ. Rian Johnson

“You had no place in this story.”

imdb.com

For the first time in nearly two decades, Star Wars evoked the childlike wonder I experienced watching the original trilogy as a youngin’: The Last Jedi is mythic and dazzling experience, and for all its faults (the poorly-written Admiral Holdo, portrayed by a well-meaning but miscast Laura Dern, being the most egregious, but the occasional clumsy plot beat also causes the movie to stumble), its storytelling—both visually and structurally—is rich and invigorating, the kind of storytelling you only get when someone with a vision is spearheading the project. Director Rian Johnson didn’t give Star Wars what it wanted; he gave Star Wars what it needed—a critical look back at its own legacy, at the stories it told and the values it perpetuated, and questioned the relationship between privilege and monomyth. Not since The Return of the Jedi have I been so excited to watch a Star Wars film over and over and over again. That’s a good feeling.

Rian Johnson honorable mention: Knives Out

45. Paterson

Dir. Jim Jarmusch

Writ. Jim Jarmusch

“Most people call it rain.”

theplaylist.net

I won’t go so far as to claim that Paterson is Jim Jarmusch’s best film (although I can’t think of one better), but it’s certainly my favorite. There isn’t much here in the way of plot: Adam Driver plays Paterson, a bus driver who lives in Paterson, New Jersey, and writes poetry in his spare time. Paterson—the film, the town, and the character—is, for the most part, content and peaceful. The best scene in the movie (heck, one of the best scenes of any movie this decade) is when Paterson encounters a young girl who shares her poetry with him. Her face lights up in an expression of pure joy, an expression of unfettered creativity; it’s one of the most uplifting slices of cinema I’ve been lucky enough to experience. Cut out the rest of the film, leave only that scene, and it would still rank highly on this list. Everything else is just gravy.

44. Over the Garden Wall

Dir. Nate Cash

“Ain’t that just the way...”

medium.com

It could be argued that Over the Garden Wall is a miniseries—it is broken up into a series of short episodes—and doesn’t rightfully belong on a list of the best films of the decade, but with a runtime of less than two hours that makes it both easy and ideal to watch in one sitting, I elected to include it here. Created by Adventure Time veteran Patrick McHale, Over the Garden Wall follows two brothers on a fairy tale-esque journey into the deep, dark woods, where they encounter all manner of strange characters and memorable musical numbers. It’s a rich, textured work which rewards repeat viewings; Cartoon Network claimed the #1 spot on my 2010-2019: The Top 50 Seasons of Television list with Steven Universe, and I am happy to give them a spot here with Over the Garden Wall. It’s an overlooked treasure.

43. Nightcrawler

Dir. Dan Gilroy

Writ. Dan Gilroy

“I will never ask you to do anything that I wouldn’t do myself.”

metro.us

Jake Gyllenhaal manifests one of the most frightening cinematic creations of the decade in Lou Bloom, a slimy, wide-eyed social scavenger who captures video footage—the gorier, the better—and sells it to news stations, crawling his way up the capitalist ladder with a “pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps” attitude. Director Dan Gilroy shoots for can’t-miss satirical targets such as greed and the insatiable American hunger for blood and guts, but what Nightcrawler lacks in subtlety it makes up for in craft and charisma. Gyllenhaal has never been better, and James Newton Howard delivers something I can’t recall ever hearing before: a morally ambiguous score. Despite feeling antiquated in its focus on news media rather than social media, this is a chilling thriller and a supreme piece of entertainment. You won’t be able to look away...unfortunately, that’s exactly what Lou Bloom wants.

42. Mommy

Dir. Xavier Dolan

Writ. Xavier Dolan

“We still love each other, right?”

pinterest.com

Mommy wears its heart on its sleeve; director Xavier Dolan doesn’t know the meaning of cynicism, so if you can’t deal with the unironic usage of songs such as “Wonderwall” and “Born to Die,” this is not the movie for you. But it is a movie for me. Anne Dorval, Antoine-Olivier Pilon, and Suzanne Clément are unforgettable as a single mother, her troubled teenage son, and the neighbor who becomes tangled up in their lives, and Dolan makes use of a claustrophobic aspect ratio to create at least a couple scenes which rank among the best of the decade. This is a wild, searing work of cinema, criminally overlooked outside the film community—if its inclusion on this list encourages even one more person to watch, then I will have done my job. I hope you love it like I do. If nothing else, it will at least stay with you.

41. The Lobster

Dir. Yorgos Lanthimos

Writ. Yorgos Lanthimos, Efthymis Filippou

“A wolf and a penguin could never live together, nor could a camel and a hippopotamus. That would be absurd.”

rogerebert.com

Yorgos Lanthimos transitions to English-language filmmaking with yet another deliciously outlandish high concept: in a utopian—sorry, uh, dystopian—future, single people are brought to The Hotel, where they are transformed into an animal of their choice if they fail to find a romantic partner within forty-five days. The satire of The Lobster is less opaque than, say, Dogtooth; the movie is blunter, but it’s also funnier and is an equal opportunist in its mockery—those who are single and those who are in relationships are both lampooned, because The Lobster’s ultimate target is a culture which has accumulated a baffling set of mores around romance. Lanthimos’ filmmaking is crisp and clean, and Colin Farrell and Rachel Weisz turn in performances which may be their best in years. The Lobster is a fiendish delight.

Yorgos Lanthimos honorable mentions: Dogtooth, The Favourite

40. Leviathan

Dir. Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Véréna Paravel

Writ. Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Véréna Paravel

“Upon earth there is not his like, who is made without fear.”

www2.bfi.org.uk

Yes, I put Leviathan (2012) on a list of the decade’s best films and left off Leviathan (2014). Deal with it. This documentary has no talking heads or conventional narrative structure. It plunges you, quite literally, into the daily work of an Atlantic fishing vessel: the camera observes sloshing blood and gore and overhears the chatter of the crew. A fish head slides across a slick surface. Seagulls screech. Chains clatter. Darkness reigns. Leviathan contains one of the funniest scenes of the decade, but it does little to lighten the oppression and claustrophobia. I wasn’t lucky enough to see Leviathan in theaters, where I suspect the existential dread it evokes would be most profound, but it remains a stark reminder of humanity’s position as apex predator of planet Earth. To be any other living creature in this world is to live under the reign of cruel and uncaring gods. The only blessing they bestow is death; the bodies are swallowed by the sea.

39. Inception

Dir. Christopher Nolan

Writ. Christopher Nolan

“Wake me up!”

everymoviehasalesson.com

Inception’s shortcomings have been thrown into sharper and sharper relief over the years—who could forget Leonardo DiCaprio shouting vague exposition during an action sequence?—but it remains a cultural touchstone (it literally added a new definition to the word “inception”!) and one of this decade’s most distinctive visual experiences. Ten years later, it’s also easy to forget what made Inception so mind-blowing. Dreams within dreams! The hallway sequence! The diegetic music woven into Hans Zimmer’s score! The antagonist is a subconscious manifestation of the protagonist’s dead wife! The ending that tricked unobservant viewers into thinking it was ambiguous! No, it’s not the masterpiece it was once made out to be. But it remains one of the most iconic and most important films in Nolan’s oeuvre, and it remains one of Nolan’s best films, the work of an accomplished storyteller working with a blank check for the first time. Leaving Inception off a list of the decade’s best movies would be borderline criminal.

Christopher Nolan honorable mention: Dunkirk

38. How to Train Your Dragon

Dir. Chris Sanders, Dean DeBlois

Writ. Cressida Cowell, Chris Sanders, Dean DeBlois, Will Davies

“I looked at him, and I saw myself.”

rogerebert.com

With the release of Kung Fu Panda in 2008, it became clear that DreamWorks Animation was attempting to tell stories that were richer and more emotionally complex than their previous output—not nearly on par with Pixar, but moving in that direction regardless—and How to Train Your Dragon, still their most accomplished film a decade later in 2020, solidified that change. The story is relatively simple: a young Viking, raised in a culture in which he is expected to kill dragons, instead befriends one. But that story is textured with elegant grace notes (my favorite is when Hiccup reaches out to touch Toothless for the first time and the dragon twitches back before meeting his hand) and thrilling aerial sequences; to this day, seeing the “test drive” scene in 3D is one of the best experiences I’ve ever had in a theater. And then there’s How to Train Your Dragon’s ace in the hole—John Powell’s soaring score, which would rank among the best of the decade if I were making a list for soundtracks. Pixar still claimed the Oscar for Best Animated Feature in 2010 for Toy Story 3, but the better film belonged to DreamWorks Animation. Come on: we all know it’s true.

37. The Grey

Dir. Joe Carnahan

Writ. Joe Carnahan, Ian Mackenzie Jeffers

“Once more into the fray. Into the last good fight I’ll ever know. Live and die on this day. Live and die on this day.”

npr.org

The Grey has all the trappings of low-budget run-of-the-mill horror, but beneath those trappings is a film of uncommon sensitivity and grace with some lovely artistic flourishes: the screen flickers to black and the audio cuts out as Liam Neeson’s plane crashes, and a clever bit of framing misdirects the viewer until a key reveal late in the movie. The horror elements are serviceable, unremarkable, but they get the job done and are relatively unobtrusive (they are refreshingly grounded, at least, being neither human nor supernatural). I love The Grey because it reminds me of what is possible when a high concept (“Liam Neeson fights wolves!”) is approached with care, craftsmanship, and attention to the fundamentals of storytelling rather than an over-reliance on cheap tricks. It may be simple, but it is effective, and it remains the high point of director Joe Carnahan’s career and Neeson’s post-Taken career. An overlooked gem, and yes—one of the decade’s best films.

36. The Tale

Dir. Jennifer Fox

Writ. Jennifer Fox

“I’m the hero of this story.”

variety.com

To reflect upon the 2010s is to reflect upon the ways in which our culture is designed to enable and protect rapists and sexual predators; as such, I considered Erin Lee Carr’s At the Heart of Gold: Inside the USA Gymnastics Scandal for this list—its courtroom sequences are incendiary and unforgettable, but I found the rest of the documentary too rote to justify an appearance here. The Tale, a dramatized memoir written and directed by Jennifer Fox, is a richer and more well-rounded experience, portraying her encounters with a man who repeatedly raped her as a child and her efforts as an adult to reckon with the trauma of those encounters. Laura Dern and Isabelle Nélisse turn in riveting performances as adult Jennifer and child Jennifer, respectively, and the film does an exceptional job showcasing the necessity of narrative; it demonstrates how stories are used to seduce, gaslight, and manipulate, but it also reaffirms how the stories we tell ourselves are crucial to our understanding of the world. Few movies this decade were more difficult to watch. Few were more needed.

35. Phantom Thread

Dir. Paul Thomas Anderson

Writ. Paul Thomas Anderson

“Whatever you do, do it carefully.”

johnnyalucard.com

The Master is arguably Paul Thomas Anderson’s greatest achievement in film this decade (it unarguably contains one of the greatest scenes this decade), but it remains to me a cold and inaccessible movie; I am more interested in the liminal spaces inhabited by Phantom Thread, which rests comfortably in the discomfort of personalities and how they grate against one another. The relationship between Reynolds and Alma is almost allegorical, a mockery of fragile masculinity which nevertheless strives to nurture and cultivate through love rather than acidity and viciousness. Daniel Day-Lewis is predictably excellent, as is Lesley Manville, but the real standout her is Vicky Krieps, who turns in one of the richest, warmest, most textured—and most overlooked—performances of the decade. Phantom Thread lacks the grandeur of Magnolia or There Will Be Blood and the self-assured swagger of Punch Drunk Love or Inherent Vice, but it asserts itself quietly and confidently as one of Paul Thomas Anderson’s most crucial works.

Paul Thomas Anderson honorable mention: The Master

34. Force Majeure

Dir. Ruben Östlund

Writ. Ruben Östlund

“I don’t share that interpretation of events.”

brightwalldarkroom.com

I’m a sucker for killer high concepts, and Force Majeure has one of them: in a moment of panic during what appears to be a life-or-death scenario at a ski resort, a husband and father flees his family instead of protecting them. The remainder of the film ruthlessly critiques the concept of masculinity and what it means in the modern world; it’s incisive and outrageously funny (in the way that Eskil Vogt and Roy Andersson are outrageously funny—your mileage may vary), and its deconstruction of gender roles is complemented by an exploration of how our lives can be dictated be mere seconds of miscalculation or poor judgment. The whole package is sharply written, shot, acted, and edited; Force Majeure is one of this decade’s best non-English movies.

33. Drive

Dir. Nicolas Winding Refn

Writ. Hossein Amini, James Sallis

“My hands are a little dirty.”

npr.org

Step aside, Bronson. Ryan Gosling exudes cool as the unnamed getaway driver in Nicolas Winding Refn’s best film, a rather unremarkable story of crime and romance directed with such style that it nevertheless carves out a space for itself in the cinematic landscape. Carey Mulligan. Oscar Isaac. Albert Brooks. Bryan Cranston. Christina Hendricks. Ron Perlman. The gloves. The jacket. The music. The elevator scene: a mini-masterclass in visual storytelling. The glamour stripped away in moments of sudden, shocking violence. What can I say? This is the movie equivalent of the “you vs. the guy she tells you not to worry about” meme. And you know what? He can have her. I’ll never look that good with a toothpick. “I don’t sit in while you’re running it down. I don’t carry a gun. I drive.”

32. Enter the Void

Dir. Gaspar Noé

Writ. Gaspar Noé

“They say you fly when you die.”

rogerebert.com

Like Upstream Color, Enter the Void is a film which I had to watch multiple times before I began to fully appreciate it. Like The Tribe, it’s a movie which requires you to re-learn how to consume a cinematic experience; it will test your patience and it will test your tolerance. Filmed from first and second person perspectives, you follow and become an American drug dealer who is shot and killed by police in Tokyo—his spirit then leaves his body and journeys between past, present, and future on the ultimate psychedelic trip. It’s a flashy, garish experience with no room for subtlety (the opening credits are the cinematic equivalent of someone screaming in your face), but this is a Gasper Noe joint and that’s part of the package: you’re here to see something you’ve never seen before. I love Enter the Void for its audacity. I love Enter the Void for its sheer madness. I love Enter the Void because it makes your friends say “What the fuck?” and because it kills any chance you had at a second date. You can keep your snobby French films and your masochistic Russian movies—give me CG penises, CG vaginas, and CG cumshots! Give me ENTER THE VOID!

31. Amour

Dir. Michael Haneke

Writ. Michael Haneke

“Things will go on, and then one day it will all be over.”

blog.cinemaautopsy.com

Michael Haneke is a reliably great filmmaker (The White Ribbon was also in contention for this list), but Amour may be his greatest work: an exacting exploration of unconditional love between an elderly couple after one of them suffers a stroke and becomes partially paralyzed. But what makes Amour truly transcendent is not how it explores love when health fails, but how it explores love when society fails. Many of us in the early 21st century live in cultures which value life more than quality of life, and Amour ruthlessly challenges and undermines the traditions which have perpetuated and entrenched that notion. Haneke does this through the use of lengthy shots which are always framed and blocked in such a way that they get your brain churning—my favorite comes in the first few minutes of the film, when the camera stays fixed on the audience during an orchestral performance. Amour refuses to allow the viewer the comfort of conventional perspectives in both the literal and the metaphorical sense, and the result is a movie which will linger in your mind and haunt you long after the credits roll. This Palme d’Or winner isn’t an unforgettable film so much as an unshakable film, and it easily ranks among the best of the decade. You don’t want to miss it.

Michael Haneke honorable mention: The White Ribbon

30. Happy Hour

Dir. Ryūsuke Hamaguchi

Writ. Tomoyuki Takahashi, Ryūsuke Hamaguchi, Tadashi Nohara

“It’s beautiful on a clear day.”

nytimes.com

What we talk about when we talk about Happy Hour: the 317-minute runtime (that’s a bit over five hours, for those of you keeping track at home). But this is a film that needs to be five hours long, and those hours fly by once you sink into its world. Director Ryūsuke Hamaguchi follows four Japanese women, all close friends, whose relationship begins to fall apart when one of them seeks a divorce. The inciting incident comes nearly ninety minutes into the movie; through scenes that run twenty, thirty, sometimes forty minutes long, Hamaguchi invites you into the intimacy and nuances of friendship—beautifully portrayed by actresses Sachie Tanaka, Hazuki Kikuchi, Maiko Mihara, and most of all the magnetic Rira Kawamura. Like Edward Yang and Abdellatif Kechiche, Hamaguchi has a particular talent for composing his images—which are always precisely, exquisitely framed—so that they appear natural, almost casual, as if he wandered into the room with a camera and just happened to start filming. The result is a rich, immersive experience that feels fully-realized and more intimate than epic. Happy Hour may not have the bombast or the majesty of this decade’s other cinematic heavy hitters, but it carves out space for an achievement all its own: an achievement in sweetness and solidarity.

29. Computer Chess

Dir. Andrew Bujalski

Writ. Andrew Bujalski

“Between a human being and a person? My money’s on the computer.”

rogerebert.com

Like the Twin Peaks episode that never was, Andrew Bujalski’s Computer Chess seems relatively normal at first glance: filmed like a 1980s faux-documentary focusing on a group of programmers who pit their computers against one another in games of chess, it slowly evolves (or devolves, depending on your perspective) into...something else entirely. A frame seems slightly out of place. Did you imagine it? The image splits for a second. No, you didn’t imagine it. Something is The descent into wrong madness begins. (???) Clues, here and there, reward the attentive viewer: ATTENTIVE. notquite horror, although it gets under your skin // humorous the makings of a Classic Cult classic. Do you think a human human human being will ever beat a person at chess? error 404: page not love found about this // fever dream Sly, smart, visionary work, but playful & not up its own ass like beyond the black rainbow. Excuse me, we have the room reserved for a chess tournament? Everything is normal here. Sex? No, we’re not interested.

28. Antiporno

Dir. Sion Sono

Writ. Sion Sono

“Cut!”

letterboxd.com

Sion Sono (who directed at least a half-dozen films this decade which could have been in contention for this list) goes full Lynch in the bizarre, beguiling Antiporno. I won’t explain what this movie is about. I’m not sure I could explain what this movie is about. It starts with a woman who lives in a colorful room and adheres to a strict schedule, and it only gets weirder and wilder from there. It’s deliciously meta. It speaks to nature of performance—not just in art, but in our everyday lives—and the masks we put on to make ourselves presentable to others...and to ourselves. Antiporno is never what you think it is, and it ascends to something resembling allegory as it morphs through its various incarnations and meditates on the nature of existence. I’m not sure what to make of it. But I know that it is hypnotic, enthralling, and unforgettable, and I know that it connected with me. Then again, who wouldn’t connect with this? If there’s anything we humans have in common, it’s the desire to scream into the void and smash one’s head into a cake. Some days you’re the person. Some days you’re the cake.

Sion Sono honorable mentions: Love Exposure, Why Don’t You Play in Hell?, Tokyo Tribe

27. Tower

Dir. Keith Maitland

Writ. Sarah Wilson, Keith Maitland

“I guess this is it. I guess this is the end.”

rogerebert.com

The Act of Killing, The Look of Silence, and O.J.: Made in America will likely go down in history as the defining documentaries of the decade, but nothing topped Tower for me. Mass shootings continued to be inextricable from American culture in the 2010s—Tower goes back to the beginning, to the University of Texas shooting in 1966, and dramatizes the event through rotoscoped interviews and re-enactments. It does not seek to explain or make sense of mass shootings; instead, it zeroes on the individual stories of those who were involved and explores how they became connected or were torn apart, how they confronted their own mortality and reckoned with years of trauma in the aftermath. Every aspect of Tower is sensitive and thoughtful, and it contains a moment—I won’t spoil it here even though you will likely see it coming—which ranks among the most devastating gut-punches of the decade. This is a gold standard for documentary filmmaking: an ambitious and fully-realized nonfiction narrative with a unique perspective, brought to life with both honesty and grace. If you watch any documentary from the 2010s, this is it.

26. Inside Out

Dir. Pete Docter

Writ. Pete Docter, Josh Cooley, Ronnie del Carmen, Meg LeFauve

“I just wanted Riley to be happy.”